Our Thanks to:

Walker Bennett, SF Author

June 03, 2008 03:54 PM EDT

"A loud noise still makes me dive for cover 36 years later. When I

lived in Louisville, Ft. Knox was 40 miles away. When they had

tank target practice, I'd spend a lot of time under the table."

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/video/2008/05/30/VI2008053002640.html?sid=ST2008060203019

By Ann Scott Tyson

W ashington Post Staff Writer

Tuesday, June 3, 2008; Page A01

Wounded Soldiers Housed Next to Firing Range

More than 170 soldiers with physical and mental wounds such as

post-traumatic stress disorder are housed across the street from

a string of firing ranges at Fort Benning, Ga., one of the Army's main

training bases. Several soldiers with PTSD said the loud gunfire at

day and night startles them and keeps them on edge and wake,

harming their recovery.

FORT BENNING, Ga. -- Army Sgt. Jonathan Strickland sits in his

room at noon with the blinds drawn, seeking the sleep that has

eluded him since he was knocked out by the blast of a Baghdad car

bomb.

Like many of the wounded soldiers living in the newly built "warrior

transition" barracks here, the soft-spoken 25-year-old suffers from

post-traumatic stress disorder. But even as Strickland and his

comrades struggle with nightmares, anxiety and flashbacks from

their wartime experiences, the sounds of gunfire have followed them

here, just outside their windows.

Across the street from their assigned housing, about 200 yards

away, are some of the Army infantry's main firing ranges, and

day and night, several days each week, barrages from rifles and

machine guns echo around Strickland's building. The noise makes

the wounded cringe, startle in their formations, and stay awake

and on edge, according to several soldiers interviewed at the

barracks last month. The gunfire recently sent one soldier to the

emergency room with an anxiety attack, they said.

"You hear a lot of shots, it puts you in a defensive mode," said

Strickland, who spent a year with an infantry platoon in Baghdad

and has since received a diagnosis of PTSD from the military. He

now takes medicine for anxiety and insomnia. "My heart

starts racing and I get all excited and irritable," he said, adding

that the adrenaline surge "puts me back in that mind frame that I

am actually there."

"Fort Benning is a training unit, so there is gunfire around us all

the time," said Elaine Kelley, a behavioral health supervisor at the

base hospital. If a soldier had a severe problem, it would have

been identified, she said.

Lt. Col. Sean Mulcahey, who recently took command of the

Warrior Transition Battalion, where wounded soldiers are

assigned, said: "No soldier has talked with me about the ranges."

If it is an issue, "we will address it," he said, stressing that the

battalion's mission is " getting those soldiers to heal."

Under Army rules, commanders of warrior transition units are

supposed to enforce "quiet hours." Officials said the location of the

barracks for wounded soldiers, along with a $1.2 million Soldier and

Family Assistance Center, was chosen for its proximity to central

facilities such as the hospital. About 350 soldiers are assigned to the

battalion--including 176 who live in the barracks near the ranges--

where they stay an average of eight months, Mulcahey said. An

estimated 10 to 15 percent of the soldiers have PTSD, he said.

Soldiers interviewed said complaints to medical personnel at

Fort Benning's Martin Army Community Hospital and officers in

their chain of command have brought no relief, prompting one

soldier's father to contact The Washington Post. Fort Benning

officials said that they were unaware of specific complaints but that

decisions about housing and treatment for soldiers with PTSD

depend on the severity of each case. They said day and night

training must continue as new soldiers arrive and the Army grows.

The soldiers are part of a growing group of an estimated 150,000

combat veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan who have

PTSD symptoms. The mental disorder has been diagnosed in

nearly 40,000 of them.

PTSD symptoms include flashbacks and anxiety, and noises such as

fireworks or a car backfiring can make sufferers feel as though they

are back in combat. Health experts say that housing soldiers near a

firing range subjects them to a continual trigger for PTSD.

"It would definitely traumatize them," said Harold McRae, a

psychotherapist in Columbus, Ga., who counsels dozens of soldiers

with PTSD who are at Fort Benning. "It would be like you having

a major car wreck on the interstate" and then living in a home

overlooking the freeway, he said. "Every time you hear a wreck

or the brakes lock up, you are traumatized."

Fort Benning, which covers more than 180,000 acres, is one of

the Army's main training bases, with 67 live-fire ranges. The base

has thousands of housing and barracks units. "There is no excuse"

for the housing situation, said Paul Ragan, an associate professor

of psychology at Vanderbilt University, who treats veterans with

PTSD. "Charitably put, it's very untherapeutic."

CONTINUED Next >

For more information

The toll-free Veterans Affairs Department Suicide hotline number

is 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Veterans Affairs Department: http://www.va.gov/

Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America: http://www.iava.org/

------------------------------------------------>

Flashback, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Suicide,

and the Lessons of WAR-- by Penny Coleman

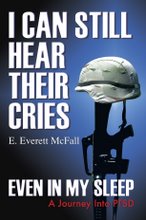

and---> I Can Still Hear Thier Cries, Even In My Sleep

... A Journey Into PTSD --By E. Everett McFall

Both Books are Available on Amazon.com

Tuesday, June 3, 2008

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)