By Jennifer Litz Editor

The founders of the new PTSD treatment center in San Angelo,

First Gulf War veteran Steve Olness and paramedic Rosendo

"Rosey" Velez. ( Photo/Sarah Balderas)

Combating P.T.S.D. and Preventing Suicides

One of the most progressive treatment centers for Post Traumatic

Stress Disorders in the country is coming to San Angelo, made

possible by an $80,000 grant from the TRIAD Fund of Permian

Basin Area Foundation. But what’s really special about the new

center at 2607 Johnson Street is not its christening by foundation

funds. The people conducting counseling services there are not your

typical government bureaucratic types. They’re veterans of war,

and even Ground Zero.

Gulf War vet Steve Olness is program manger for veteran’s services

for Mental Health Mental Retardation Services of the Concho Valley.

MHMR will share digs on Johnson Street with Emergency Services

Respite Center to provide care for recently returned soldiers and

other crisis responders suffering from Post Traumatic Stress

Disorder.

“I was in the army in the first Gulf War, and when we came back,

there was nothing like this,” says Olness. “Our war was nothing

like this one, but there was nobody waiting to try to get you used

to civilian life again. Or get you used to peacetime. There wasn’t

anything. We just came back, and a lot of guys who got out of the

military right after that, you got a handshake and goodbye.”

Olness says the soldiers coming back from tours in Iraq and

Afghanistan are going to need lot of help—and so are the military

resources set up to receive them.

“It’s going to be like a tidal wave,” Olness says. “Because some

of these kids are pulling three, four, and five tours over

there. And when you pull an 18-year-old kid fresh out of high

school, send him to training and he goes to a combat area, and

all he knows is what he was taught to do, sometimes that means

he has to take another person’s life. And then he comes back

home, and everyone lauds him as a hero—but he doesn’t feel

like a hero.”

Olness says there’s a stigma to having PTSD. “If a [solider comes

back with] diagnosed PTSD, the military has to pay ‘x’ number

of dollars for the rest of his life,” he says. “It is easier for them

to say, ‘You’re not doing your job; you’re late for formation; I hear

you’ve had problems with your wife . . .’, they take the easy way...

because it’s easier to put him out of the military and give him

limited benefits if any at all.”

Olness says the new program will offer counseling to vets without

the stigma. “If you’re on active duty, you get labeled right away,”

he says. “You don’t want to be the NCO that is in charge of troops

that’s the guy that can’t handle it. He’s done his time in combat, and

now he’s training other troops, and you don’t want to be trained by

a guy who can’t take it.” The program created with TRIAD funds

features counselors and doctors on staff who can see patients and

even prescribe medicine. Many staffers are veterans themselves.

The Problem with the VA

Pat Dugan was a reconnaissance marine corporal in Vietnam for

19 months, starting in 1966. “There’s a big difference between

being a combat person and a non-combat person,” explains Pat

Dugan. “I’m a marine, and I’m proud to be a marine, but I’m

even more proud to be a combat marine.” He’s now a

passionate voice for veteran help that resounds throughout

West Texas. Dugan says the problem with the Department

of Veteran’s Affairs, is that they haven’t delivered on

the promise, such as: the military will take care of you for

your service.

Instead, Dugan, like Olness, paints the picture of a disrespectful,

mainly incompetent VA system. He foresees bad times ahead

for the “kids” currently turning several tours, who will come home

to bureaucratic red tape rather than help from government agencies.

“I am seeing one of the biggest mushroom clouds,” Dugan says of

times ahead for Iraq/Afghanistan veterans. “’Cause I’m thinking,

the public runs around with yellow ribbons on their cars, but what

I don’t see, except with Congressman Ciro Rodriguez (TX-23), is

people realizing that everyone in this war has PTSD. Because there

are no front lines in this war. You can be [in a non-combat service]

and get your butt blown off the road there with anyone else.

Everyone’s sitting around waiting for an explosion to go off, and

they send you back and back for more tours.”

When these vets do come back home—or in between myriad

deployments—they’re still fighting—for their benefits. “In

Del Rio, for example, we’ve got people with problems,”

Dugan says. “And they have to travel 150 miles to get help

[at a VA clinic]. And then when you get up there, I’m not being mean,

but when you go up there and apply to get help, you get some

VA muffin that’s not a veteran, and they put you through mental

gymnastics like you wouldn’t believe. [Vets] don’t want to be

humiliated and go through that process.”

Dugan praises programs like the new MHMR/ESRC building.

He can even name one state agency that does things right—

The Texas Veteran’s Commission, whom he sees as a shining

example for others like it.

“I think the Texas Veteran’s Commission is as fine as any in

the US,” he says. “They treated me with dignity and respect,

talked with me, and took their time with me. They are an

example.” Conversely, Dugan describes nightmarish situations

at Audie Murphy Memorial Veterans Hospital and others.

During one visit, Dugan was chastised loudly for allowing an

80-year-old woman on oxygen to cut ahead of him for treatment.

Another time, Dugan was rebuked for offering his Marine Corps

serial number as identification. “We don’t use those anymore, we

only use social security numbers,” an administrator scoffed. But

Dugan says the Corps had taught him to be proud of his serial

number. Everyone has a social security number; Dugan felt he

earned that serial number.

“I was so pissed off, I came home and gave my Jack Russell

Terrier my serial number, so now he’s 2164539USMC,” Dugan

says. “That was my rebuke to the VA.” But not only do many

vets express their feeling that VA administrators, many of who

have never served, lack respect for veterans, they also lack some

basic “industry” knowledge. “One of my friends had a Navy Cross

—it’s the second highest medal awarded, for an extreme act of

heroism,” Dugan says. He walked into the VA, and the lady asked

him [about a combat action ribbon]. She said they didn’t issue those

until ’71, and he had gotten out of the service in ‘69. So she says,

‘Do you have any proof that you saw combat?’ And he said, ‘I got a

Navy Cross, does that count?’ And she said, [thinking is was akin to

a Blue Cross/Blue Shield policy]

‘Did I ask you about your insurance? I asked you about your

Combat Action Ribbon!’ She didn’t even know what a Navy

Cross was. She thought it was insurance.”

------------------------------------>

The VA has set up a 24-hour suicide hotline

round-the-clockaccess to mental health professionals.

The number is 1-800-273- 8255 (TALK).

To learn more about PTSD-- visit the

National Center for PTSD website.

------------------------------------>

Flashback, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Suicide,

and the Lessons of WAR by Penny Coleman

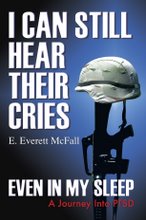

and--->I Can Still Hear Thier Cries, Even In My Sleep...

A Journey Into PTSD By E. Everett McFall

Both Books are Available on Amazon.com

Posted by E. Everett McFall at 10:28 PM